Indelible Winter

➾ Official Selection | Austin Spotlight Film Festival | January 24, 2018

Palpitations of Dust

➾ Official Selection | Logcinema Art Films | Jan 13-14, 2018

➾ Semi-Finalist | German United Film Festival | January 1, 2018

➾ Honorary Mention (Experimental) | Los Angeles Film Awards | December 2017

➾ Pre-Selection | Singapore International Film Festival | December 2017

➾ Official Selection (Experimental) | Near Nazareth Festival | December 13-17, 2017

➾ Pre-Selection | Rome Film Awards | October 18, 2017

➾ Winner (Experimental) | Laughlin International Film Festival | October 12-15, 2017

➾ Official Selection | San Pedro Film Festival | October 8, 2017

➾ Semi-Finalist | Madrid Art Film Festival | September 29-30, 2017

➾ Semi-Finalist | Cinema London | September 22, 2017

➾ Official Selection | Festival Angelica | September 18-24, 2017

➾ Best Experimental Project Nomination | Action on Film Festival | August 24-26, 2017

➾ Best Sound Design (Short) Nomination, Best Supporting Actor (Short) Nomination | Hollywood Dreamz International Film Festival | August 24-26, 2017

➾ Semi-Finalist | Malta Film Festival | August 24-25, 2017

➾ Best Experimental Short Film | Prince of Prestige Academy Award | July 29, 2017

➾ Best Director (Short Film) Nomination, Best Actor Nomination, Best Director Nomination | World Music & Independent Film Festival | July 22-30, 2017

➾ Official Selection (Narrative) | Synimatica Short Film Festival | July 15-30, 2017

➾ Official Selection | California Women’s Film Festival | July 14-16, 2017

➾ Talented New Filmmaker Nomination | Nice International Film Festival | May 18, 2017

➾ Official Selection (Autumn Session) | Auckland International Film Festival | Autumn 2017

➾ Nomination | Taste Awards | February 20, 2017

➾ Official Selection | Hollywood Reel Independent Film Festival | February 17, 2017

➾ Best Experimental Film | Los Angeles Cinema Festival of Hollywood | January 11, 2017

➾ Official Selection (Short Film) | 5th Mumbai Shorts International Film Festival | December 21, 2016

➾ Best Experimental Film | Los Angeles Film & Script Festival | November 5, 2016

➾ Winner of Award of Recognition (Experimental) | IndieFEST | October 11, 2016

About Ann Huang

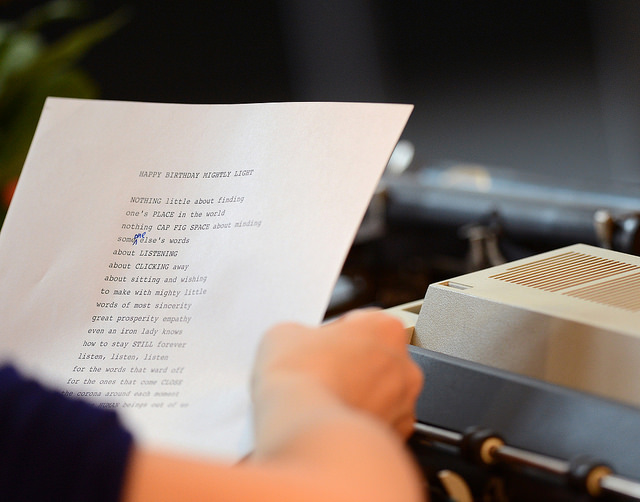

Ann Huang is a filmmaker based in Newport Beach, Southern California. Huang was born in Mainland China and raised in Mexico and the US. World literature and theatrical performances became dominating forces during her linguistic training at various educational institutions. Huang possesses a unique global perspective on the past, present and future of Latin America, the United States and China. She is an MFA candidate from the Vermont College of Fine Arts and has authored one chapbook and two poetry collections. Huang’s debut experimental short film “PALPITATIONS OF DUST” won the Best Experimental Film in 2017 PAECA (Prince of Prestige Academy Award), Best Award in Los Angeles Film & Script Festival, and Best Experimental Film in LA Cinema Festival of Hollywood. For more information, visit http://annhuang.com.