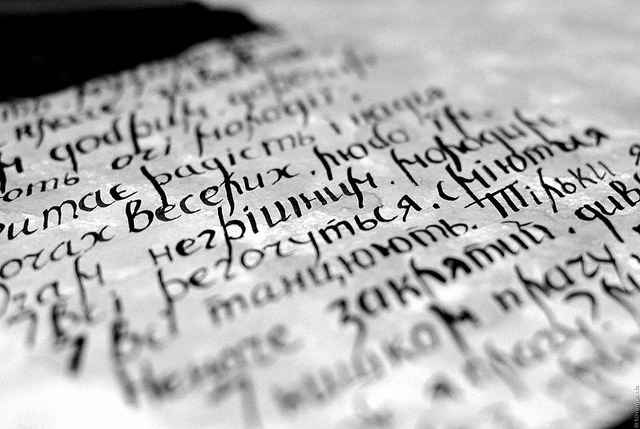

Language is a barrier in more than one respect. If you’re in a foreign country and can’t speak the native language, you might find it difficult to communicate. These barriers sometimes form when words are translated from one language into another. You can find extreme examples of this on some imported products, like a warning label for plum jelly that states, “1. Please do not attract one grain by to swallow. 2. Below five years old, please not edible.” These phrases might make perfect sense in the original language, but the literal translation ends up being a source of confusion and amusement. The same happens with varying degrees with translated poems. As a result, scholars often debate the effectiveness of translations.

Blurred Lines

When done correctly, translations are wonder devices that open doors to new worlds. They are essential to introducing readers to new cultures and ideas. Without them, you might not be exposed great works, like Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Candide by Voltaire, or Laozi’s Tao Te Ching. Poet Haroldo de Campos was celebrated for his masterful translations of some of the Western world’s most important works into Portuguese, such as those by Mallarmé, Dante, Homer and James Joyce.

The problem with translations generally stems from the fact that you are dependent upon a translator’s subjective interpretation. You rely on this individual’s understanding of the poet’s language, dialect, culture, life, target audience, historical period and more. You trust that the translator fully understood the original work and remained faithful to its essence and voice. You have faith that the translator is on par with the poet’s artistic abilities and has a good understanding of the new target readers and their culture.

When a translator fails to be faithful to the original work, it becomes the translator’s poem—a completely new work. When this occurs, interesting things happen. For example, a culture might adopt the translated piece as an original work. An example of this is John Dryden’s version of the epic Aeneid by Virgil. In the preface, Dryden stated that he tried to make Virgil sound English, as if he were from Great Britain. He turned the original unrhymed verses into couplets while using lines from Sir John Denham’s translation. Dryden rewrote Virgil’s work to appeal to an audience in a different period that had a different language and culture. He made the audience the priority. The losses in translation remain invisible to those who don’t take it upon themselves to do a careful comparison.

When an original poem and its translation clash, there is often a failure on the translator’s part to read for meaning and the language. This ultimately hurts the audience, but creates opportunities for additional translations. While a translator cannot change a poet’s original work, the individual can present his or her own interpretation.

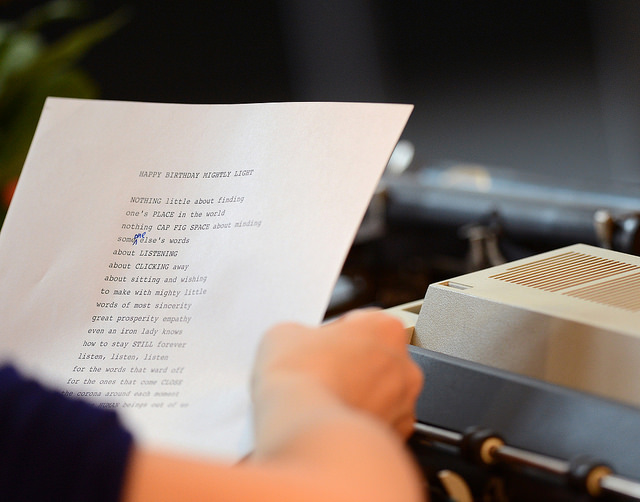

Translations are like artistic mimicry. While it is possible to translate poetry, it is important to keep in mind that no translation will ever be the original work. Therefore, there is always room for reexamination and improvement. Rather than give up on reading translations, get your hand on as many as you can find. Read the introductory essays written by the translators to learn what guided their work and made it unique. Soak in the words and draw your own conclusions about original poet’s words.

Examples of Translated Poems

“The Song of Despair”

By Pablo Neruda, translated by W.S. Merwin

The memory of you emerges from the night around me.

The river mingles its stubborn lament with the sea.

Deserted like the wharves at dawn.

It is the hour of departure, oh deserted one!

Cold flower heads are raining over my heart.

Oh pit of debris, fierce cave of the shipwrecked.

In you the wars and the flights accumulated.

From you the wings of the song birds rose.

You swallowed everything, like distance.

Like the sea, like time. In you everything sank!

It was the happy hour of assault and the kiss.

The hour of the spell that blazed like a lighthouse.

Pilot’s dread, fury of a blind diver,

turbulent drunkenness of love, in you everything sank!

In the childhood of mist my soul, winged and wounded.

Lost discoverer, in you everything sank!

You girdled sorrow, you clung to desire,

sadness stunned you, in you everything sank!

I made the wall of shadow draw back,

beyond desire and act, I walked on.

Oh flesh, my own flesh, woman whom I loved and lost,

I summon you in the moist hour, I raise my song to you.

Like a jar you housed the infinite tenderness,

and the infinite oblivion shattered you like a jar.

There was the black solitude of the islands,

and there, woman of love, your arms took me in.

There were thirst and hunger, and you were the fruit.

There were grief and the ruins, and you were the miracle.

Ah woman, I do not know how you could contain me

in the earth of your soul, in the cross of your arms!

How terrible and brief was my desire of you!

How difficult and drunken, how tensed and avid.

Cemetery of kisses, there is still fire in your tombs,

still the fruited boughs burn, pecked at by birds.

Oh the bitten mouth, oh the kissed limbs,

oh the hungering teeth, oh the entwined bodies.

Oh the mad coupling of hope and force

in which we merged and despaired.

And the tenderness, light as water and as flour.

And the word scarcely begun on the lips.

This was my destiny and in it was the voyage of my longing,

and in it my longing fell, in you everything sank!

Oh pit of debris, everything fell into you,

what sorrow did you not express, in what sorrow are you not drowned!

From billow to billow you still called and sang.

Standing like a sailor in the prow of a vessel.

You still flowered in songs, you still broke in currents.

Oh pit of debris, open and bitter well.

Pale blind diver, luckless slinger,

lost discoverer, in you everything sank!

It is the hour of departure, the hard cold hour

which the night fastens to all the timetables.

The rustling belt of the sea girdles the shore.

Cold stars heave up, black birds migrate.

Deserted like the wharves at dawn.

Only the tremulous shadow twists in my hands.

Oh farther than everything. Oh farther than everything.

It is the hour of departure. Oh abandoned one.

“Tonight I Can Write the Saddest Lines”

By Pablo Neruda, translated by W.S. Merwin

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

Write, for example, ‘The night is starry

and the stars are blue and shiver in the distance.’

The night wind revolves in the sky and sings.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

I loved her, and sometimes she loved me too.

Through nights like this one I held her in my arms.

I kissed her again and again under the endless sky.

She loved me, sometimes I loved her too.

How could one not have loved her great still eyes.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

To think that I do not have her. To feel that I have lost her.

To hear the immense night, still more immense without her.

And the verse falls to the soul like dew to the pasture.

What does it matter that my love could not keep her.

The night is starry and she is not with me.

This is all. In the distance someone is singing. In the distance.

My soul is not satisfied that it has lost her.

My sight tries to find her as though to bring her closer.

My heart looks for her, and she is not with me.

The same night whitening the same trees.

We, of that time, are no longer the same.

I no longer love her, that’s certain, but how I loved her.

My voice tried to find the wind to touch her hearing.

Another’s. She will be another’s. As she was before my kisses.

Her voice, her bright body. Her infinite eyes.

I no longer love her, that’s certain, but maybe I love her.

Love is so short, forgetting is so long.

Because through nights like this one I held her in my arms

my soul is not satisfied that it has lost her.

Though this be the last pain that she makes me suffer

and these the last verses that I write for her.

“The Shape of Your Eyes”

By Paul Eluard, translated by Mary Ann Caws

The shape of your eyes goes round my heart,

A round of dance and sweetness.

Halo of time, cradle nightly and sure

No longer do I know what I’ve lived,

Your eyes have not always seen me.

Leaves of day and moss of dew,

Reeds of wind and scented smiles,

Wings lighting up the world,

Boats laden with sky and sea,

Hunters of sound and sources of colour,

Scents the echoes of a covey of dawns

Recumbent on the straw of stars,

As the day depends on innocence

The world relies on your pure sight

All my blood courses in its glance.

“I Love”

By Jacques-Bernard Brunius, translated by Mary Ann Caws

I love sliding I love upsetting everything

I love coming in I love sighing

I love taming the furtive manes of hair

I love hot I love tenuous

I love supple I love infernal

I love sugared but elastic the curtain of springs turning to glass

I love pearl I love skin

I love tempest I love pupil

I love benevolent seal long-distance swimmer

I love oval I love struggling

I love shining I love breaking

I love the smoking spark silk vanilla mouth to mouth

I love blue I love known—knowing

I love lazy I love spherical

I love liquid beating drum sun if it wavers

I love to the left I love in the fire

I love because I love at the edges

I love forever many times Just one

I love freely I love especially

I love separately I love scandalously

I love similarly obscurely uniquely

HOPINGLY

I love I shall love

In the United States, a trainer is an individual who teaches skills. In Great Britain, it is an athletic shoe. A bog in the U.S. is a swamp. In Great Britain, it’s a toilet. In Oregon, a buggy is an old-fashioned term for a stroller, horse carriage or car. In North Carolina, it’s a modern term for a shopping cart.

In the United States, a trainer is an individual who teaches skills. In Great Britain, it is an athletic shoe. A bog in the U.S. is a swamp. In Great Britain, it’s a toilet. In Oregon, a buggy is an old-fashioned term for a stroller, horse carriage or car. In North Carolina, it’s a modern term for a shopping cart.